At BalletMet, we are celebrating Women’s History Month by shining a spotlight on five forces of 20th century ballet.

Written by Sara Wagenmaker

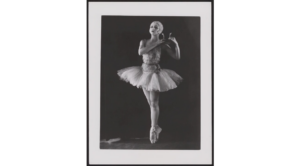

Alexandra Danilova

Today, we look back at Alexandra Danilova, an influential educator and talented performer.

Born Aleksandra Dionisyevna Danilova on November 20, 1903, her training began in 1912 Russia, at the Imperial School of Ballet. Persevering through the Russian Revolution in her youth, she danced with the Soviet State Ballet upon graduation. She then toured Europe with the Soviet State Dancers for a few months in 1924 before joining Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, a ballet company that brought together artists of many mediums to create extraordinary theatrical collaborations.

In the group of Russian dancers was George Balanchine, a prominent choreographer and (after his split from Tamara Geva) Danilova’s lover. The two never officially married. They were separated by 1933, when Balanchine moved to America. Danilova married twice in her life, first to Giuseppe Massera in 1934 and then again to Kazimir Kokich in 1941. Both marriages ended. Kokich would later name her the godmother of his daughter, Kim.

Alexandra joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo as a prima ballerina in 1938, working closely with dancer Frederic Franklin. She was featured prominently in pieces like Léonide Massine’s Gaîté Parisienne, where her glamour and charm won over audiences. Initially, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo toured extensively. During World War II, however, they restricted themselves to America. They travelled throughout the country, bringing ballet to new audiences and sparking American interest in the art form. Danilova was able to become an American citizen in 1946. Through the next eleven years, she would guest with numerous companies and even start her own group, Great Moments of Ballet. She also appeared in some Broadway shows and musical comedies, although few were commercially successful. Danilova retired from ballet performance in 1958. Throughout her performing career, she had originated roles in works including Apollon Musagète, La Pastorale, The Triumph of Neptune, Le Beau Danube, Jardin Public, and Capriccio Espangnol.

In 1964, she ran into George Balanchine once again. The two had worked together on and off since their 1933 split. Balanchine was now widely recognized for his choreographic skills and had established a school for ballet in New York, which today is known as the School of American Ballet. He was looking for teachers. Luckily, she was looking for work.

Alexandra became a core part of the School of American Ballet, establishing performance workshops and staging many Balanchine and Petipa works. According to the Kennedy Center, she recognized that “a talent for teaching [is] a separate talent, different from the kind that makes a great performer.” Danilova had both of these talents in spades. She was an excellent teacher for SAB in particular because not only did she had the same training foundation as Balanchine, but had also worked with him throughout his early choreographic endeavors and was familiar with his style. Her own extensive career beyond Balanchine’s works opened her up to a multitude of perspectives on ballet that she could incorporate into her instruction. With her knowledge, she was able to guide young dancers’ development of the technical skills and dedicated mindset necessary to succeed in the ballet world. Her work with students was instrumental in establishing America as a center of ballet.

In her later years, Alexandra wrote an autobiography. Choura, titled after a nickname of hers, provided her perspective on her life and career. A documentary about her was also made, 1986’s Reflections on Dance. She retired from teaching in 1989. That same year she was awarded the Kennedy Center Honors in recognition of her achievements. On July 13, 1997, Alexandra Danilova—an impressive teacher and beautiful performer who traveled the world with ballet—died in New York City.

LEARN MORE

Choura

Alexandra Danilova | Kennedy Center (kennedy-center.org)

Prima Ballerina (July 2000) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin (loc.gov)

FAMED BALLET DANCER, TEACHER ALEXANDRA DANILOVA DIES – The Washington Post

Alexandra Danilova, Ballerina and Teacher, Dies at 93 – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Photograph of Alexandra Danilova in Apollo, n.d. ?, no photographer. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200181829/>.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tamara Geva

Tamara Geva was a skilled ballerina and theatrical star.

Tamara Geva was born Tamara Levkievna Gevergeyeva on March 17, 1906. Her childhood was tumultuous. Although her father was quite wealthy due to his manufacturing business, he did not marry her mother until Tamara was 6 years old. Her mother carried on many affairs before and during the marriage. In addition to the already-strained relationship of her parents, Tamara grew up during the tumultuous Russian Revolution, in which her father lost much of his wealth.

Her governess Rosalia managed to persuade Tamara’s parents to allow their daughter private ballet lessons. After the Revolution, when the State Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet opened up enrollment to non-Christians, Tamara began taking night classes at the school. She was 13 at the time. There, she met George Balanchine, a young man with an eye for choreography. She married him in 1923, at age 17. Tamara joined a small dance group that he had started, then called “Evenings with the Young Ballet”, where he tried his early choreographic experiments. Tamara and some of her fellow students (including Alexandra Danilova and George Balanchine) then joined the Soviet State Dancers, which left Russia to tour Europe in 1924.

During this tour, several of the dancers auditioned for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. They joined the troupe rather than return to Russia. However, Diaghilev did not give Tamara very many opportunities. She decided to leave Diaghilev for Nikita Balieff’s group La Chauve-Souris. This artistic career choice contributed to her split from Balanchine. Although they could not officially divorce, as their marriage papers were still in Russia, they both considered their romantic relationship over and moved on to other things.

La Chauve-Souris was a touring revue that presented a mix of dancing, singing, and sketches. In 1927 they toured to America, where Tamara performed two Balanchine solos—the first American performance of Balanchine choreography. Her deft movement in the unconventional choreography began to attract attention. American audiences did not yet know who George Balanchine was, but through Tamara’s brilliant dancing, they received a glimpse of the future.

Tamara quickly began to move into theatrical and film work. The diverse skillset required by La Chauve-Souris enabled her to develop a keen adaptability as a dancer and actress. Any character was hers to become—any role, hers to master. She entered Broadway with Whoopee (1928), Three’s a Crowd (1930) and Flying Colors (1932), but made her largest splash with the hit musical On Your Toes. Written by Rodgers and Hart and featuring the musical number Slaughter on Tenth Avenue choreographed by George Balanchine, Tamara’s performance received rave reviews. The New York Times’ Brooks Atkinson described her as “so magnificent as the mistress of the dance that she can burlesque it with the authority of an artist on a holiday”. On Your Toes was one of the first shows to incorporate dance into the storyline: a monumental turning point for the art of musical theatre.

After a guest appearance with Balanchine’s American Ballet in 1935, Tamara kept her attention on film and theatre work. Her film credits include Their Big Moment (1934), Manhattan Merry-Go-Round (1937) and Orchestra Wives (1942). Onstage, she appeared in Idiot’s Delight (1938), Trojan Women (1941), No Exit (1947), and Misalliance (1953). She took creative control of a few productions, choreographing the 1946 Ben Hecht film Specter of the Rose and authoring a musical comedy with Haila Stoddard and Dana Suesse in 1959, Come Play with Me. Her artistic influence was prominent in these films and plays, where she brought her quick wit to every production. Tamara’s range was frequently noted—both as a dancer and an actress, there seemed to be no limit to what she could portray. The broadness of her work is testament to her versatile skill.

In her American career, she married twice more. Her second marriage, to fashion executive Kapa Davidoff, ended in divorce, as did her third marriage to actor John Emery. Tamara had no children.

With a personality described as acerbic, outspoken, and, at the same time, charming, Tamara was a force on and offstage. Her life is chronicled in her 1972 autobiography Split Seconds. Her last onscreen appearance was in 1983’s Frevel. She passed away in Manhattan on December 9, 1997 at 91, leaving behind a sizeable legacy spanning film, theatre, and dance.

LEARN MORE

Split Seconds

Tamara Geva Is Dead at 91; Ballet Dancer and Actress – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Farewell To Diva Geva, Dancer-Actress Dies at 91 | Playbill

DANCE VIEW; THE STORY OF A DANCER’S EARLY LIFE IN RUSSIA – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Tamara Geva, a Russian-born dancer and a | AP News

New York Public Library Digital Collections

IMDB

Genthe, Arnold, photographer. Geva, Tamara, Miss, portrait photograph. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2018715716/>.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

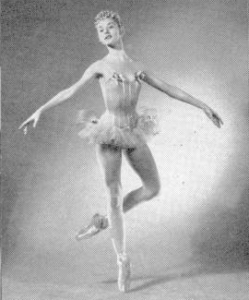

Vera Zorina

Vera Zorina: film star, dancer, and director.

Vera Zorina was born Eva Brigitta Hartwig in Berlin on January 2, 1917. Her musical parents, the German Frederick and Norwegian Billie Hartwig, readily brought her into the arts. She debuted onstage as the First Fairy in Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1930, at age 14. He cast her once again in 1931’s Tales of Hoffman. Vera soon moved to London to study dance more intensely, under the direction of Marie Rambert and Nicholas Legat.

Anton Dolin, a British dancer in Ballets Russes, invited her to perform opposite him in 1931’s Ballerina. After Ballerina, she changed her name to Vera Zorina and joined Colonel de Basil’s Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, a group formed after the dissolution of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. During this time, the resident choreographer Léonide Massine had an open marriage with his wife Eugenia Delarova; he was quick to involve the 18-year-old Vera in his relationship.

While with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Vera was featured in Massine works including La Boutique Fantasque, Le Beau Danube, and Les Présages. Notably, she also danced in Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces. Nijinska’s choreography took advantage of Igor Stravinsky’s foreboding score to create a powerful work, blending ritualistic folk dances with balletic ideas for a ballet that remains cutting edge even today.

In 1936, Vera left ballet for the theatre, starring in a London production of On Your Toes. Vera rapidly made a name for herself in this new art form. Samuel Goldwyn even flew her out to America for The Goldwyn Follies (1938). Samuel had plenty of funds at his disposal, allowing him to fill the film’s credits with master artists: a score from George Gershwin, a script from Ben Hecht, actors including Adolphe Menjou, the Ritz Brothers, Andrea Leeds, & Edgar Bergen, and choreography from none other than George Balanchine.

Vera and George quickly fell into a romance. Her appearance in The Goldwyn Follies’ Water Nymph Ballet, where she rose from a pool dripping in a clinging gold tunic, brought a sensuality out of her dancing that continued into her relationship with the choreographer. Although their dynamic was turbulent, with frequent fights, the two soon married and lasted for nearly a decade before divorcing in 1946.

Her career continued with Broadway productions and films including the Rodgers and Hart musical I Married An Angel, the film adaptation of On Your Toes, Louisiana Purchase, Follow the Boys, Dream With Music, The Tempest, and Lover Come Back. Balanchine would contribute choreography to many of these productions. Vera had hopes of becoming a serious ballerina or a dramatic actress, but the public’s cool reception of her Terpsichore in the 1943 run of Apollo and her replacement by Ingrid Bergman in a film adaptation of For Whom The Bell Tolls solidly ended them.

She married her second husband in 1946, Goddard Lieberson. He would soon become the president of CBS Records. They had two sons during their marriage. Unfortunately, both Goddard and their son Jonathan died before Vera. She married for the third and final time to Paul Wolfe, a harpsichordist.

In 1990 she moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Performance was long behind her, but she continued to connect to the arts through dramatic narration. She narrated works including Arthur Honegger’s Jeanne d’Arc Au Bûcher, Claude Debussy’s Le Martyre De Saint-Sebastien, and, for the New York City Ballet’s 1982 Stravinsky Festival, André Gide’s Perséphone. She also worked as an opera director, directing productions at the Santa Fe Opera, New York City Opera, and the Norwegian Opera. Vera’s film, theatre, and ballet credits all contributed to a vast artistic understanding and keen sense of drama—keys to her success in shaping operatic productions.

Upon her death in April of 2003, she was survived by her husband, a son, and three granddaughters. Her glamour, her intellect, and her seductive screen presence fill not only the pages of her 1986 memoir Zorina, but also each frame of her every film.

LEARN MORE

Zorina

Vera Zorina, Ballet Dancer Who Helped Bring Classical Dance to Musicals, Dead at 86 | Playbill

Vera Zorina | | The Guardian

Vera Zorina, 86, Is Dead; Ballerina for Balanchine – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Vera Zorina in Balanchine’s (Undine) Water Nymph Ballet

IMDB

Publicity photo for Star Spangled Rhythm 1942

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Maria Tallchief

One of the first American ballerinas to win worldwide renown, Maria Tallchief was a part of the Five Moons and a key figure in Chicago’s early ballet scene.

Maria Tallchief, born Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief or Ki He Kah Stah Tsa on January 24, 1925, grew up in a small town located on the Osage Nation reservation. Fairfax, Oklahoma was the site of an oil discovery during her father Alexander’s youth. As a result, she and her sisters grew up with plenty of wealth.

The family spent their summers in Colorado Springs, where she and her sister Marjorie began taking ballet. Their mother Ruth encouraged their artistic development. Maria took piano lessons as well and, for a time, had hopes of becoming a concert pianist. The family moved to Beverly Hills, California when she was 8, where she began to focus more on her dance practice.

Maria then began training with Ernest Belcher. Throughout her life as a dancer, she would encounter numerous teachers who each poked at her weak technical foundation, including George Balanchine. Her classes as a child had not, apparently, provided a very good ballet education. Ernest was the first teacher to work with her to correct her faulty training. After a few years with him, Maria began taking classes with Bronislava Nijinska. Nijinska was an incredibly innovative choreographer and dancer who grew up in Russia and traveled throughout Europe, before settling in America to teach and create dance. Maria studied under her for five years. Upon graduating from high school, her father refused to pay for college, and so she moved to New York City in the hopes of finding a job.

In 1942, Maria Tallchief joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Through this company, Maria met many rising choreographers. Her teacher Nijinska choreographed several works for the group, which Maria would perform in. Maria also performed Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo. Rodeo told the story of love, loss, and rejection on a Western ranch, blending different dance techniques to portray Americana onstage. George Balanchine, her first husband, choreographed many works for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. They met through the company in 1944 and were married by 1946. Maria was initially surprised by his unexpected proposal, as she felt their relationship was mostly professional.

In the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Maria (who then was still going by her birth name) faced pressure to change her name to Talchieva to seem more Russian. Proud of her name and her heritage, she initially refused. Over time, however, she compromised by turning Elizabeth Marie into Maria and Tall Chief into Tallchief. Even so, her Osage lineage was important to her and she remained connected to her people and culture throughout her career.

She spent a season guesting with the Paris Opera before returning to the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Once her contract was up, she returned to New York City to dance with Balanchine’s fledgling company Ballet Society (now known as the New York City Ballet). She made a name for herself in her electric performance in Firebird (1949). Each performance: she would dance, the curtain would go down, and the crowd would roar. Throughout the ‘40s and ‘50s, Maria worked with Balanchine on pieces including The Four Temperaments, Symphonie Concertante, Orpheus, Swan Lake, Serenade, Scotch Symphony, and premiere his Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker. Even after their 1950 divorce and during Maria’s brief marriage to Elmourza Natirboff, they continued in their professional work until Maria’s departure from the stage in 1966.

Maria worked with companies including American Ballet Theatre, Ruth Page’s Chicago Opera Ballet, the San Francisco Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet and the Hamburg Ballet, partnering with dancers Erik Bruhn, Nicholas Magallanes, André Eglevsky, and Rudolph Nureyev to perform works like Jardin aux lilas and Miss Julie. She also portrayed Anna Pavlova in a 1952 film Million Dollar Mermaid.

Although she retired in 1966, Maria would eventually return to the performing arts. She settled in Chicago with her third husband Henry Paschen, Jr. and their daughter Elise. She became the ballet director at the Lyric Opera in 1971, a role she would fill for two decades. Maria formed the dancers at the Lyric Opera into the Chicago City Ballet in 1974. This company lasted 13 years, laying the groundwork for other Chicago ballet companies to find success. Chicago’s rich dance history, including the origin of house dance and home of landmark companies like Joffrey Ballet and Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, would not be complete without her.

Her many accomplishments were recognized by the Osage Nation in 1953 with the title Princess Wa-Txthe-thonba (the Woman of Two Worlds). Maria was one of five indigenous ballerinas from Oklahoma to gain renown. The others were Myra Yvonne Chouteau, Rosella Hightower, Moscelyne Larkin, and her sister, Marjorie. These ballerinas are often referred to as the Five Moons. All five of these women made powerful strides towards equality in their lifetimes.

Maria received further recognition through the declaration of June 29th as Maria Tallchief Day by the Oklahoma State Senate. In 1996, she was awarded a Kennedy Center Honor and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Multiple magazines including Newsweek featured her in profiles, and Makah Tribe member Sandra Sunrising Osawa and her husband Yasu Osawa released a 2007 documentary about her life titled Maria Tallchief. Maria wrote her own story in her autobiography, Maria Tallchief: America’s Prima Ballerina. She passed away in Chicago on April 11, 2013.

LEARN MORE

Maria Tallchief: America’s Prima Ballerina

Maria Tallchief: Osage Prima Ballerina | Headlines and Heroes (loc.gov)

Maria Tallchief, Dazzling Ballerina, Dies at 88 – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Maria Tallchief | Kennedy Center (kennedy-center.org)

https://www.chicagodancehistory.org/

Photo credit: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maria-Tallchief/images-videos#/media/1/581592/18813

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tanaquil Le Clercq

Today, we look back at Tanaquil Le Clercq, a brilliant performer and an inspiring muse to many choreographers.

She was born in Paris on October 2, 1929. At the age of 3, her parents (a French academic father and an American debutante mother) brought her to New York. She soon began taking ballet. Tanaquil’s first teacher was Mikhail Mordkin, previously of the Bolshoi Ballet. At age 10, in 1941, she won a scholarship to the School of American Ballet.

Her instructors immediately noticed her potential. Tanaquil soon caught the eye of George Balanchine himself—founder of the school and director of the New York City Ballet. She was briefly tempted by Paris in her early career but was pressured by family and others to return to New York City, where Tanaquil performed with NYCB frequently as a student. By 19, she was a principal dancer, and by 23, she was married to George. He was 48 years old.

She was featured in many ballets and had numerous roles created for her, including The Nutcracker’s Dewdrop. The spritely variation showed off the crisp attack of her movements and her immense skill as a dancer. Other notable roles of Tanaquil’s include Choleric in Four Temperaments, Symphony in C, La Valse, Western Symphony, and Divertimento No. 15. In addition to these Balanchine works, she premiered choreography from Jerome Robbins and Merce Cunningham and performed the work of Frederick Ashton and Anthony Tudor. Her performance in Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun, danced alongside Francisco Moncion, received much praise from critics and inspired the title of a later documentary about her.

Critics loved Tanaquil. Audiences loved Tanaquil. George Balanchine loved Tanaquil, although their marriage became strained going into the mid-1950s. But in the eyes of the public, according to Politico and critic Marie-Françoise Christout, Tanaquil Le Clercq “could be compared to no other contemporary ballerina.” Her career was on a startling trajectory—but it abruptly changed course in 1956.

Three weeks after her 27th birthday, she took the stage for the last time. The company was in Denmark, at the tail end of an exhausting tour. After an October performance she was suddenly unable to walk. Tanaquil was rushed to the hospital; it was polio. She was paralyzed. Her fame was such that even the queen of Denmark visited her hospital bed. Despite her many visitors and all their well wishes, she would never walk again.

Her husband searched for some type of cure, trying all sorts of physical therapies and regimens to help her get the care she needed. George held hopes that she would regain the use of her legs. Some of these exercises would inspire movements in his ballets, like 1957’s Agon. However, as time went on, it became apparent that his hopes of her recovery were in vain. They divorced in 1969. Over time, they became friends once more. George ended up leaving large sums and royalties to her in his will.

In her life, Tanaquil had had brief romances with Jerome Robbins and the composer Juriaan Andriessen, although neither resulted in marriage.

After retiring from the stage, Tanaquil mostly withdrew from the public eye. She gave few interviews and, after her years of celebrity, preferred to keep her life private. Those who knew her described her as living in each moment rather than reminiscing. She wrote two books (Mourka: The Autobiography of a Cat and The Ballet Cook Book). In 1974 Tanaquil joined the faculty of Dance Theatre of Harlem, a company started by Arthur Mitchell. Arthur and Tanaquil had danced together at NYCB. She taught ballet from a wheelchair, using her hands to show the movements to the students, until finally retiring in 1982. She also found joy in photography and crosswords. Between her writing, her teaching, and her everyday approach to life, Tanaquil’s artistry continued long after her performances ended.

The author Varley O’Connor wrote a fictionalized novelization of her life after polio, The Master’s Muse. Nancy Buirski’s 2013 film Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq uses interviews and archival footage to tell Tanaquil’s story. In 2021, Orel Protopopescu released another book about her, Dancing Past the Light: The Life of Tanaquil Le Clercq. Tanaquil herself left no autobiography. She died in Manhattan on December 31, 2000. Her impact as an inspiration to key choreographers of the period is not to be overlooked, nor is her powerful post-polio choice to reshape her life as her own.

LEARN MORE

Tanaquil Le Clercq; Polio Ended Dancing Career of New York City Ballet Star – Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

Muse of many faces: Ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq’s life and times, before and after Balanchine, remembered (and, now, novelized) – POLITICO

Tanaquil Le Clercq | Ballet | The Guardian

Inside the Mind of Tanaquil Le Clercq – New York Times

Paramodernities

Photo is public domain

Written by Sara Wagenmaker